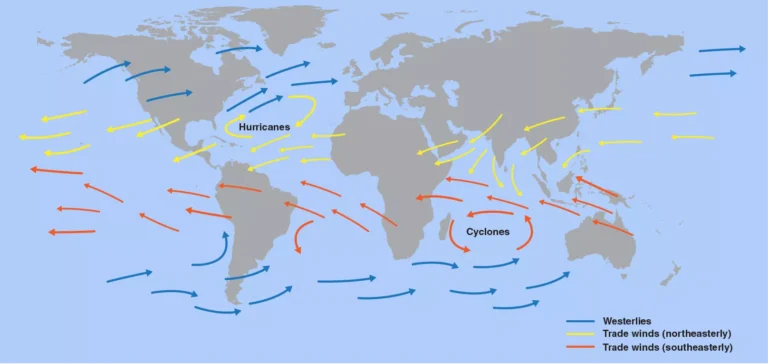

The map shows the great belts of wind that circle the planet: the trade winds near the equator and the westerlies in the mid‑latitudes of each hemisphere. These winds steer powerful storms such as hurricanes and tropical cyclones, creating dangerous conditions for people and infrastructure along their paths.

What the map shows

The map uses three main arrow colors to show global wind patterns over the oceans. Blue arrows mark the westerlies, which blow from west to east in the mid‑latitudes of both hemispheres, while yellow arrows show the northeasterly trade winds north of the equator and red arrows show the southeasterly trade winds south of the equator. In the Atlantic and Indian Oceans, circular arrow patterns highlight the favored tracks of hurricanes and cyclones as they curve away from the equator into the westerlies.

Why these winds blow

Two main physical processes create these wind belts: uneven heating of Earth’s surface by the Sun and the rotation of the planet. Near the equator, strong solar heating makes warm air rise, leaving low pressure at the surface; cooler air from higher latitudes flows in to replace it, forming surface winds that move toward the equator. As the planet spins, the Coriolis effect deflects these moving air masses—toward the right in the Northern Hemisphere and toward the left in the Southern Hemisphere—turning straight‑line flows into the curved trade winds and westerlies.

North America

Around North America, the map shows yellow arrows of the northeasterly trade winds blowing from the northeast toward the equator over the Caribbean and tropical Atlantic. These winds help organize clusters of thunderstorms into tropical depressions and, when ocean water is warm enough, into hurricanes that move westward toward the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico. Farther north, blue arrows show the westerlies sweeping storms from west to east across the United States and Canada, often curving hurricanes that leave the tropics back into the North Atlantic.

These wind patterns create difficult situations along North America’s coasts. The trade‑wind‑steered hurricanes can bring extreme rainfall, storm surge, and destructive winds to islands and coastal cities, while the westerlies can interact with these storms, accelerating them or pulling them along new paths. Over land, the same westerlies drive powerful mid‑latitude cyclones that produce blizzards, severe thunderstorms, and intense winter storms.

South America

Near South America, the yellow trade winds blow across the tropical Atlantic toward the Amazon region, bringing moist air and feeding heavy rainfall in the rainforest. Over the South Atlantic, red arrows of the southeasterly trades flow toward the equator, then curve westward, steering storms toward the northeastern coast of the continent. South of about 30°S, blue westerlies dominate, pushing weather systems and ocean waves from the Pacific, around the tip of South America, and across the South Atlantic.

These winds can create severe weather and maritime hazards. Persistent trade winds can pile warm water and humidity along the northern and eastern coasts, supporting torrential rains and occasional tropical storms. The strong westerlies in the Southern Ocean whip up huge swells and fierce gales, making navigation around Cape Horn notoriously dangerous for ships and contributing to coastal erosion and damaging surf along southern Chile and Argentina.

Europe

Across the North Atlantic toward Europe, the map illustrates blue westerly arrows sweeping from North America toward the British Isles and the rest of the continent. These westerlies carry moist oceanic air that moderates temperatures and delivers frequent storms to western Europe, especially in autumn and winter. The yellow arrows near the subtropical Atlantic indicate weaker trade winds that help guide hurricanes northward, where they can transition into extratropical storms affecting Europe days later.

The westerlies create both benefits and difficulties for Europe. They bring vital rainfall and relatively mild winters, but they also deliver powerful windstorms that can topple forests, disrupt transport, and damage coastal defenses. Occasionally, the remnants of Caribbean hurricanes that have been turned north and east by these winds arrive as intense, rain‑laden systems, causing flooding and coastal damage.

Africa

Over Africa and the adjoining oceans, yellow northeasterly trades cross the Sahara and Sahel toward the equatorial Atlantic, while red southeasterly trades blow northward from the South Atlantic. Where these trade winds meet near the equator, they create a zone of rising air and thunderstorms known as the Intertropical Convergence Zone, which migrates north and south with the seasons. Many of the tropical disturbances that later become Atlantic hurricanes begin as clusters of storms along this belt west of Africa.

These winds bring both life‑giving rains and hazardous conditions. When the convergence zone shifts north, moist trade winds can produce the African monsoon, vital for agriculture but also capable of severe floods. At the same time, strong dry northeasterly winds—the Harmattan—can carry dust from the Sahara across West Africa and out over the Atlantic, reducing visibility and air quality. Over the Indian Ocean, the trade winds and their seasonal reversal contribute to the monsoon system, which can cause catastrophic floods and landslides in East African countries.

Asia

Asia sits beneath some of the most complex wind patterns on the map. Yellow arrows show the northeasterly trades blowing across the tropical Pacific and Indian Oceans toward Southeast Asia, while red arrows south of the equator blow northwestward toward Indonesia. These trades, together with seasonal shifts in pressure patterns, form the backbone of the Asian monsoon: in summer, winds flow from ocean to land, bringing heavy rains; in winter, they reverse direction, carrying cold, dry air out from the continent.

These shifting winds create difficult situations especially in South and Southeast Asia. In the wet season, onshore winds feed intense monsoon rains that can cause river flooding, urban inundation, and deadly landslides. In the dry season, offshore winds can promote drought and poor air quality, as smoke from agricultural burning and wildfires is carried over densely populated regions. Over the Arabian Sea and Bay of Bengal, trade‑wind‑fed cyclones can strike India, Bangladesh, Myanmar, and surrounding countries with destructive winds and storm surge.

Australia and the Pacific

Around Australia and the wider South Pacific, red southeasterly trade winds blow toward the equator and then curve westward, forming a steady wind belt across the tropical ocean. Blue westerlies south of Australia race from west to east, part of the “Roaring Forties” and “Furious Fifties” famous among sailors. In the western Pacific, the trades help spin up tropical cyclones that can track toward northern Australia, the Pacific islands, or eastward toward the open ocean.

These winds shape both climate and hazards. Persistent trade winds drive ocean currents and upwelling, influencing fisheries and the health of coral reefs, but they also steer damaging tropical cyclones toward coastal communities. The strong westerlies in the Southern Ocean create powerful waves that can batter southern and western Australian coasts, erode beaches, and threaten offshore infrastructure, especially when combined with high tides and low‑pressure systems.

Why wind direction changes

The map’s curved arrows show that winds rarely move in straight lines for long. As air flows from regions of high pressure to low pressure, Earth’s rotation continually deflects it, turning equator‑bound winds into west‑blowing trades and pole‑ward winds into east‑blowing westerlies. Temperature contrasts between land and sea, and between equator and poles, constantly reshape pressure patterns, so wind direction changes with seasons and from day to day.

These changing winds matter because they determine where storms go and how strong they become. When trade winds strengthen, they can speed up ocean currents, alter sea‑surface temperatures, and feed more energy into developing tropical cyclones. When westerlies shift position or intensity, they can redirect storm tracks, bringing floods to some regions and droughts to others. For communities, this means that the same global wind belts that enable sailing, distribute rainfall, and moderate climate can also be the drivers of hurricanes, cyclones, blizzards, and powerful coastal storms that create the difficult and sometimes life‑threatening situations highlighted by the map.