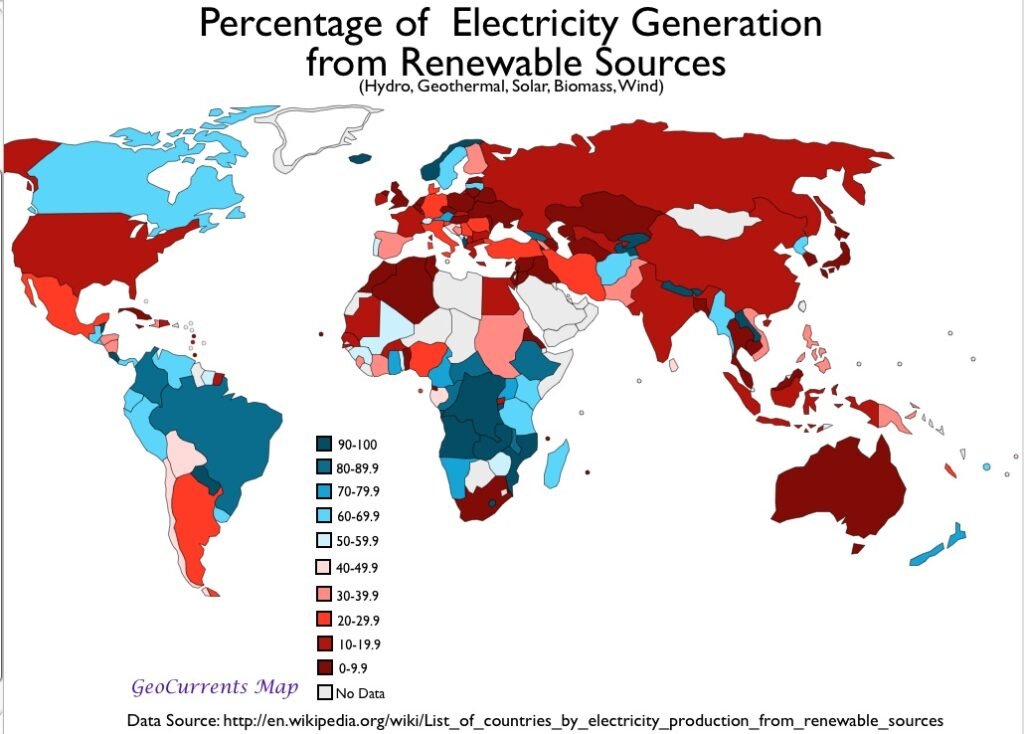

This map shows the share of each country’s electricity that comes from renewable sources such as hydro, geothermal, solar, biomass, and wind. The darker blue countries generate most of their electricity from renewables, while the darkest red countries rely overwhelmingly on fossil fuels and other non‑renewable sources.

North America

In North America, Canada and several Central American states stand out in blue, reflecting their heavy dependence on hydropower and, increasingly, wind and geothermal energy. Canada’s vast river systems and mountainous terrain make large hydroelectric dams economical, while Costa Rica and some neighbors have invested steadily in geothermal and hydro projects to reduce fuel imports. In contrast, the United States and Mexico appear in lighter or darker red shades, signaling a much lower percentage of electricity from renewables. Despite having strong wind and solar resources, both have long‑established coal, gas, and nuclear fleets, and market structures and regulations have slowed the pace at which renewables can replace this existing capacity.

South America

South America overall leans more toward blue, reflecting the long‑term dominance of hydropower in countries such as Brazil, Colombia, and Peru. Mountainous terrain and large river basins have allowed these states to build enormous dams that supply the bulk of their electricity, making renewables a central part of their power systems. However, some southern and Caribbean‑adjacent countries appear in lighter colors, which suggests a more mixed or fossil‑heavy energy mix. In these cases, limited hydro resources, weaker grids, or political and financial constraints have led to continued reliance on oil and gas power plants, especially for peak demand and remote regions.

Europe

Europe presents a patchwork of colors, ranging from dark blue leaders in renewable generation to deep red states that still depend heavily on fossil fuels. Nordic countries and a few Alpine states are typically among the highest renewable producers, thanks to abundant hydro potential, strong wind resources, and early policy support for green energy. By contrast, several industrialized countries in Western and Eastern Europe remain in darker red, reflecting decades of investment in coal, gas, and sometimes nuclear plants. These nations often face political resistance to closing existing mines and power stations, as well as social concerns about job losses in traditional energy sectors, which slows the transition despite ambitious climate targets.

Africa

Africa shows wide variation, with some central and eastern countries shaded blue, indicating a high share of hydroelectricity in their grids. Where governments have built major dams on large rivers, renewable power can dominate electricity generation even if total electricity use remains relatively low. Many North African and resource‑rich states, however, remain red or pale, signaling a heavy dependence on oil and gas. In these economies, domestic fossil resources are cheap and politically important, and limited access to investment capital makes it harder to finance large solar or wind projects, even though the physical potential for renewables is high.

Asia

Asia’s pattern is dominated by red shades across many large and industrialized economies, highlighting persistent reliance on coal and gas for electricity. Rapid economic growth in countries like China, India, and several Southeast Asian states has been powered for decades by coal‑fired plants, which were relatively cheap and scalable when these countries began their industrialization. Even where wind and solar capacity is now expanding quickly, the legacy of enormous coal fleets means that renewables still account for a modest share of total generation. In parts of Central and Western Asia, oil and gas wealth makes fossil‑fuel power plants the default choice, and subsidies for fuel further discourage rapid change.

Oceania

In Oceania, some smaller island states and New Zealand appear in more renewable‑heavy colors, reflecting strong hydro, geothermal, and emerging solar and wind sectors. Geographical isolation and high fossil‑fuel import costs have pushed some islands to explore renewables as a way to improve energy security and reduce electricity prices over time. Australia, however, tends to show a lower renewable share historically because of its abundant coal resources and long‑standing coal power infrastructure clustered near mining regions. While large‑scale solar and wind are expanding, shifting an entire national grid away from a coal‑dominated base requires substantial investment in transmission lines, storage, and flexible backup capacity.

Why many developed countries still have low renewable shares

Several developed countries on the map remain shaded in red even though they have the wealth and technology to build renewable plants. One core reason is path dependence: for decades they invested heavily in coal, gas, and nuclear stations, and those assets still have years of economic life remaining. Closing them early can be politically unpopular and financially costly, particularly in regions where fossil‑fuel industries provide many jobs and tax revenues. Another barrier is grid design and regulation; many power systems were optimized for large, centralized fossil plants, and upgrading transmission networks, storage, and market rules to integrate variable solar and wind can be complex and time‑consuming.

Policy choices also matter. Some wealthy countries have maintained fuel subsidies, lax carbon pricing, or inconsistent renewable support schemes, which keeps fossil generation competitive. Others prioritize energy security and worry that rapid closure of coal or gas plants could expose them to supply shocks, especially if storage and interconnections lag behind. As a result, even when renewables are cheap on a per‑kilowatt‑hour basis, the overall system transition moves steadily but not instantly, and the share of green electricity can remain modest for years.

Long‑run consequences of continued fossil use

If countries continue to rely heavily on biofossil fuels—coal, oil, and gas—for electricity, the long‑run consequences extend far beyond local power bills. Persistent combustion of these fuels raises concentrations of greenhouse gases, intensifying global warming and driving more frequent and severe climate‑related events such as heatwaves, storms, droughts, and sea‑level rise. These impacts create economic losses through damaged infrastructure, reduced agricultural yields, health problems from air pollution, and increased spending on disaster recovery and adaptation. Over time, societies locked into fossil‑fuel systems may also face higher energy costs as easy‑to‑access reserves decline and carbon regulations become stricter.

There are also strategic and social risks. Economies that fail to diversify away from fossil fuels risk stranded assets when global demand falls or climate policies tighten, leaving power plants, pipelines, and mines underused or obsolete. Workers and communities tied to these sectors may experience abrupt employment shocks if the transition is delayed and then occurs rapidly under crisis conditions. By contrast, a gradual and planned shift toward renewables and storage allows retraining, regional development, and industrial policies that build new value chains around clean technologies.

Rising global energy demand in the age of AI

The need for electricity will grow sharply as artificial intelligence and digital technologies expand, adding pressure to the patterns shown in this map. Training and running large AI models requires vast data centers that operate around the clock, consuming enormous amounts of power for computation and cooling. As more industries adopt AI for automation, logistics, and analytics, and as everyday devices become smarter and more connected, the total load on national grids will keep climbing. If that extra demand is met mainly with fossil‑fuel power plants, global emissions will rise even if household and transport sectors become more efficient.

Meeting this new wave of demand sustainably will require accelerating investment in renewable generation, energy storage, flexible grids, and efficiency improvements in data centers and digital infrastructure. Countries that move fastest to align AI‑driven growth with clean electricity will reduce their climate impact, improve air quality, and gain an advantage in emerging green technology industries. Those that continue to expand fossil‑based generation risk locking themselves into higher emissions, greater climate vulnerability, and rising long‑term energy and environmental costs as the digital and AI revolution unfolds.