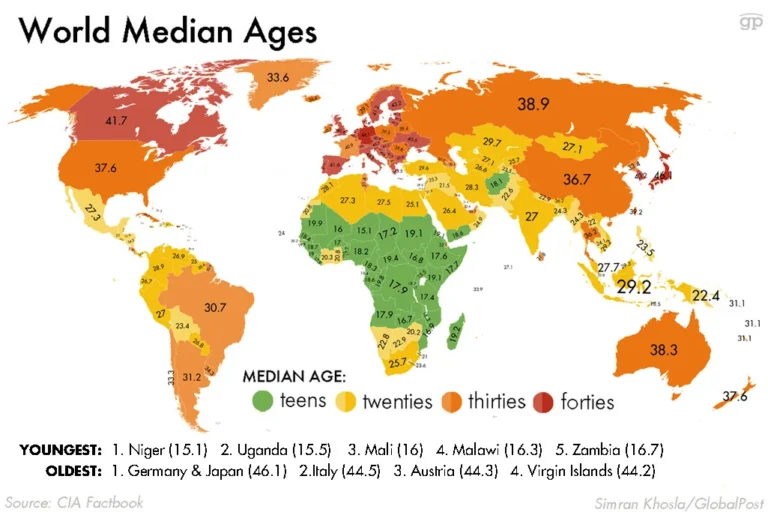

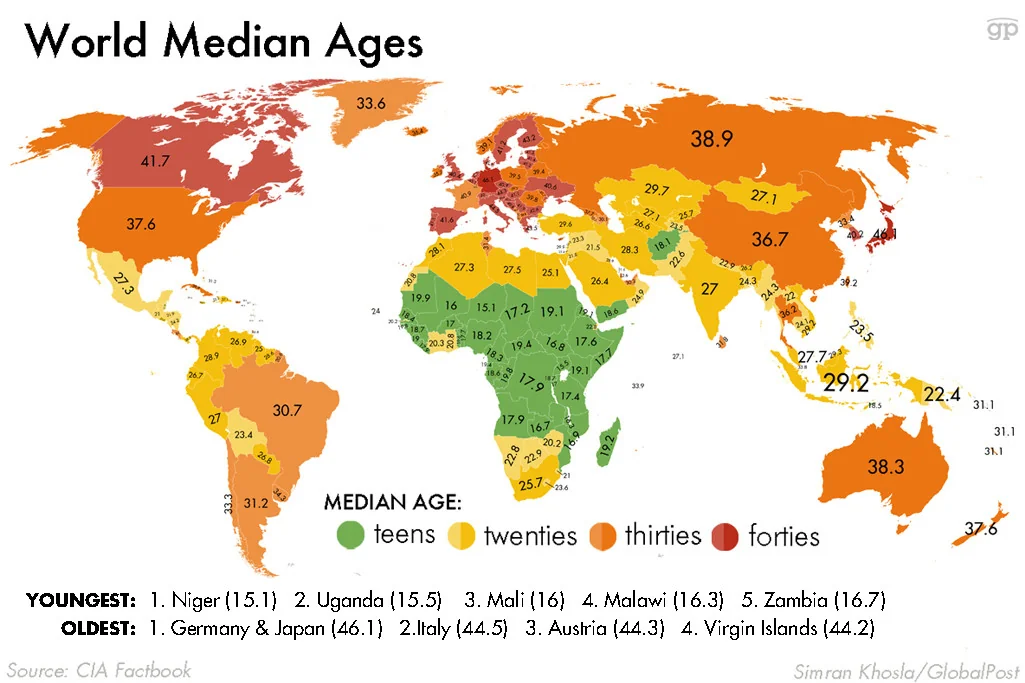

The map shows us the median age of populations around the world, with darker red shades representing countries where people are older on average and pale yellow shades indicating much younger populations. Median age is a powerful summary of a country’s demographic story because it reflects past fertility, mortality, and migration patterns as well as current social and economic conditions.

North America

North America is dominated by mid‑to‑high shades of orange and red, signaling relatively high median ages in Canada and the United States, and moderately high values in Mexico and much of Central America. These patterns are linked to long periods of declining fertility, wider access to education—especially for women—and greater use of modern contraception, all of which reduce the number of children per family. In the U.S. and Canada, extensive schooling and higher living costs encourage people to delay marriage and childbearing, pushing the median age higher as large cohorts of older adults live longer due to good healthcare.

In parts of Central America, median ages are lower than in the north but still rising as education expands, especially secondary education for girls, and as urbanization changes family norms. Where schooling is weaker and employment more informal, families tend to have more children both for cultural reasons and as a form of old‑age security, so the shift toward an older median age is slower. Religious traditions in some areas encourage large families, but as education and media exposure increase, younger generations begin to balance religious values with economic realities, gradually lowering fertility and raising the median age.

South America

Most South American countries appear in mid‑range oranges, indicating a demographic transition in progress: not as old as Europe or East Asia, but clearly older than much of Africa. Expanding access to secondary and tertiary education has played a central role here; as more young people—particularly women—stay longer in school and enter the labor market, they tend to have fewer children and to postpone motherhood, which steadily pushes median age upward. Urbanization is also crucial: the majority of South Americans now live in cities where housing is expensive, daycare is limited, and children are relatively costly to raise, further reinforcing lower fertility norms.

However, pockets of lower median age persist where educational attainment lags, inequality remains high, and rural or traditional family structures are more common. In these areas, large families may still be valued and supported by religious beliefs that discourage contraception or abortion, slowing the region’s overall aging. At the same time, improving healthcare and falling child mortality mean that more children survive into adulthood, so even with gradually falling fertility, median age may remain relatively young for a while before fully shifting into the older profile seen in richer countries.

Europe

Europe is the darkest region on the map, with many countries shaded in deep red, signaling some of the highest median ages in the world. This reflects decades of very low fertility—often well below the replacement level—combined with long life expectancy driven by strong healthcare systems and high living standards. Extensive education systems, especially broad access to higher education, encourage later entry into stable employment and delay family formation; couples often choose to have one or two children at most, if any.

Religion historically favored larger families in parts of Europe, but secularization and changing social norms have significantly weakened that influence, especially in Western and Northern Europe. Where religious institutions still hold more sway, such as in portions of Eastern or Southern Europe, economic stress, unemployment, and migration have nonetheless pushed fertility down, contributing to population aging. The result is a continent facing challenges related to shrinking workforces and rising pension and healthcare costs, with median ages climbing into the mid‑40s in several states.

Africa

Africa appears mostly in pale yellows and light oranges, signaling that it is the youngest continent by far, with median ages often in the late teens or early twenties. This youthful profile is strongly tied to high fertility rates, especially in countries where access to education—particularly for girls—is limited and where primary and secondary school completion rates remain low. When girls leave school early and marry young, they tend to have more children over their lifetimes, which keeps the age structure very young.

Religion and cultural norms also play a significant role in many African societies. In some regions, religious teachings and traditional values emphasize large families as a blessing, discourage contraception, and place high status on early marriage and motherhood. Combined with limited reproductive health services, this sustains high fertility and slows the rise of median age. Where education expands, especially where girls remain in school through adolescence and where family‑planning programs reach rural areas, fertility gradually declines, and the median age begins to creep upward, creating the potential for a future “demographic dividend” if jobs and governance improve.

Asia

Asia shows a complex mosaic: dark red in East Asia and parts of Western Asia, mid‑range orange in South and Southeast Asia, and lighter shades in some poorer or conflict‑affected countries. East Asian economies such as Japan and South Korea have some of the world’s highest median ages, driven by ultra‑low fertility and extremely long life expectancy. These societies combine intense education systems, high urban housing costs, and demanding work cultures, all of which make child‑rearing expensive and time‑consuming; many young adults therefore delay or forgo marriage and children altogether. Religion here tends to be less directly pro‑natalist than in some other regions, and social expectations around success and education can dominate family decisions.

In South Asia and parts of Southeast Asia, median ages are lower but rising as education expands and fertility drops from very high to moderate levels. Countries that have invested in female literacy, girls’ secondary schooling, and access to contraception typically show faster declines in fertility and thus quicker increases in median age. Where religious or cultural norms strongly favor early marriage and discourage family planning, fertility remains higher and the population stays younger. At the same time, economic modernization and migration to cities can quietly erode those norms, leading to smaller families even when formal religious teachings have not changed, gradually pushing the map’s colors toward deeper oranges over time.

Oceania

Oceania is split between relatively older societies like Australia and New Zealand, which appear in stronger orange or red shades, and younger Pacific island states with lighter tones. In Australia and New Zealand, high education levels, strong female labor‑force participation, and urban lifestyles in cities like Sydney and Auckland all contribute to low fertility and rising median age. Access to reliable contraception and relatively secular social attitudes frame childbearing as a choice rather than an obligation, and many couples opt for smaller families.

In several Pacific island countries, lower median ages persist because fertility remains higher and education and employment opportunities are more limited. Religious institutions often play a central role in community life and may encourage larger families or oppose certain forms of contraception, which can keep fertility above replacement level.

How education, fertility, and religion shape median age

Across all continents, three forces interact to shape the median age patterns visible on the map: education, fertility, and religion‑linked norms. Higher levels of education—especially for girls and women—consistently correlate with lower fertility because schooling raises aspirations, opens job opportunities, and increases knowledge and use of reproductive health services. When people spend more years studying, they marry later and have fewer children, and over time this produces an age structure with relatively fewer young children and larger middle‑aged and elderly cohorts, driving the median age upward.

High fertility does the opposite: when families have many children, the population pyramid becomes very wide at the base, pulling the median age downward. This pattern dominates in much of Africa and parts of South Asia and the Middle East, where large families are still common, child mortality has fallen, and each successive birth cohort is very large. Religion shapes both education and fertility by influencing family ideals, gender roles, and attitudes toward contraception and reproductive rights. Where religious or traditional beliefs strongly favor early marriage, discourage family‑planning methods, or link status and blessing to large numbers of children, fertility often stays high and median age remains low unless counterbalanced by strong educational and economic incentives for smaller families.

The map therefore is not just a snapshot of who is “young” or “old” today; it is a visual summary of deep social processes. Regions that expand quality education, empower women, and allow religious and cultural norms to evolve alongside economic realities tend to move gradually toward lower fertility and older populations. Those where schooling lags, fertility stays high, and religious or cultural pressures sustain large families will continue to have very young populations for decades, with major implications for employment, stability, and development as these large youth cohorts come of age.