The Global Debt Crisis

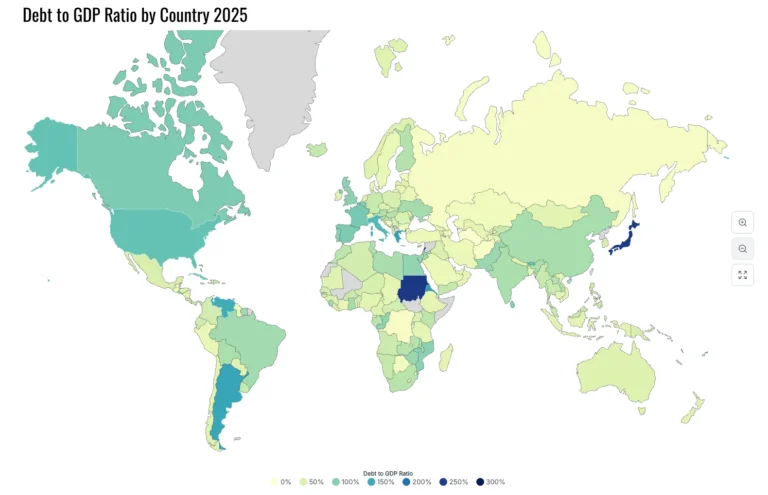

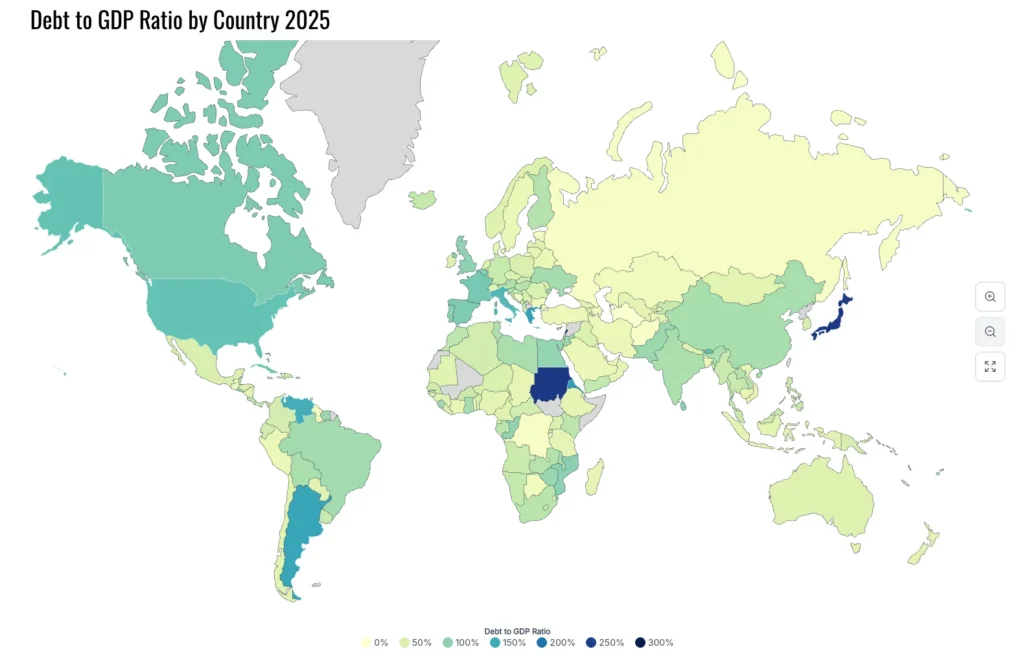

The world is drowning in debt. According to the latest data visualized in global debt-to-GDP ratios for 2025, nations across every continent are grappling with unprecedented levels of government borrowing. What’s most striking about this map isn’t just the magnitude of debt in developed economies, but the fundamental question it raises about our modern monetary system: How did we get here, and is this debt ever truly payable?

The answer lies in the inherent design of the fiat currency system that has governed global finance since the collapse of the Bretton Woods agreement in 1971. When currencies were unshackled from gold and other tangible assets, governments gained the ability to create money through debt. This system, while providing flexibility during crises, has created a perpetual cycle where debt isn’t just encouraged—it’s structurally necessary for the system to function.

North America: The Debt Superpower

North America presents a sobering picture of debt accumulation in the world’s largest economy. The United States, colored in dark teal on the map, carries a debt-to-GDP ratio exceeding 120%, representing over $34 trillion in total debt. Canada follows a similar trajectory, with debt levels in the 100-150% range.

These figures aren’t accidents of poor fiscal management but rather symptoms of a fiat system that requires constant monetary expansion. When money itself is created through the issuance of government bonds, the economy becomes addicted to debt. The U.S. Federal Reserve, like central banks worldwide, maintains this system through a delicate balance of interest rates and bond purchases, but the underlying problem remains: the debt can never truly be paid off without collapsing the monetary system itself.

The developed nature of these economies paradoxically contributes to their debt burden. With sophisticated financial markets, these nations can borrow at relatively low interest rates, making debt appear manageable in the short term. However, this creates a dangerous feedback loop where easy borrowing leads to more spending, which requires more borrowing, ad infinitum.

Europe: A Continent in Chains

Europe tells perhaps the most dramatic debt story on the global stage. The map reveals a patchwork of debt levels, with Southern European nations like Italy, Greece, Portugal, and Spain showing darker shades indicating debt-to-GDP ratios well above 100%. Greece, in particular, has become the poster child for sovereign debt crisis, having previously exceeded 200% debt-to-GDP.

The eurozone’s structure exemplifies the fundamental flaw in the fiat system. Member nations surrendered their monetary sovereignty to the European Central Bank but retained fiscal independence. This created a situation where countries could accumulate debt without the ability to devalue their currency—traditionally the escape valve for indebted nations in a pure fiat system.

Meanwhile, Japan appears in dark navy blue, representing one of the highest debt-to-GDP ratios globally, exceeding 250%. Japan’s situation is particularly instructive: despite decades of massive government debt, the country hasn’t collapsed because it borrows primarily in its own currency from its own citizens. This reveals another truth about fiat currencies—they can sustain astronomical debt levels as long as confidence in the system persists.

Asia: The Rising Debtors

Asia presents a fascinating contrast between established economies carrying heavy debt loads and emerging markets beginning their own debt journeys. Japan’s extreme debt level has already been noted, but China’s lighter green shade is perhaps more concerning for the future.

China’s official debt-to-GDP ratio appears moderate on this map, somewhere in the 50-100% range. However, this figure masks enormous hidden debt at the provincial and local government levels, along with debt held by state-owned enterprises. When including these less visible liabilities, some estimates place China’s true debt burden above 300% of GDP.

India, colored in lighter tones, shows a more modest debt profile, but the trajectory is concerning. As one of the world’s fastest-growing major economies, India is rapidly accumulating debt to finance infrastructure, development programs, and now, economic stimulus measures. The fiat currency system makes this borrowing seem painless in the present, but the compounding effect of interest payments will burden future generations.

The pattern is clear: as economies develop and embrace the global fiat financial system, they invariably take on more debt. This isn’t because developing nations are fiscally irresponsible—it’s because the modern economic playbook, written by developed nations, requires deficit spending and monetary expansion to generate growth.

Africa and South America: The Emerging Debt Trap

Africa and South America display relatively lighter shades on the map, with most countries showing debt-to-GDP ratios below 100%. However, this apparent fiscal health is misleading. These continents face a different debt challenge: much of their borrowing is denominated in foreign currencies, making them vulnerable to currency fluctuations and capital flight.

Argentina, shown in darker blue along South America’s eastern coast, has repeatedly defaulted on its debt obligations, illustrating the fragility of emerging market debt. When countries cannot print the currency in which they owe money, the debt becomes genuinely unsustainable rather than merely perpetually growing.

African nations, mostly in lighter greens and yellows, are increasingly borrowing for development—often from China’s Belt and Road Initiative. As these economies grow and integrate further into the global financial system, they too will face the structural debt trap that ensnares developed nations.

Why Developed Countries Lead in Debt

The correlation between economic development and debt levels isn’t coincidental. Developed countries have more debt for several interconnected reasons rooted in the fiat system itself.

First, developed nations have deeper financial markets that can absorb large amounts of government bonds. Pension funds, insurance companies, and foreign governments eagerly purchase this debt, making borrowing easy and relatively cheap.

Second, these countries have demonstrated the ability and willingness to service their debt obligations, creating confidence that allows for ever-higher borrowing. This confidence is self-reinforcing until suddenly it isn’t—as Greece discovered.

Third, developed economies have become dependent on deficit spending to maintain their welfare states, military expenditures, and economic stimulus programs. Politicians face electoral consequences for cutting spending but can obscure the cost of borrowing, especially when central banks keep interest rates artificially low.

Most fundamentally, the fiat currency system requires constant money creation to function. Since money is created through debt in this system, economic growth becomes synonymous with debt growth. Developed countries, having been in this system longer, simply have more accumulated debt.

The Unsustainable Trajectory

The map of global debt-to-GDP ratios reveals an uncomfortable truth: we are witnessing a worldwide experiment in monetary policy with no historical precedent. Never before have all major economies simultaneously carried such high debt levels in currencies backed by nothing but faith in government institutions.

The fiat system has enabled this debt accumulation by severing the connection between money and tangible value. Governments can “kick the can down the road” indefinitely, refinancing old debt with new debt, as long as confidence persists. But this creates a fragile system vulnerable to loss of faith, demographic changes that reduce the working-age population relative to retirees, or economic shocks that require even more borrowing.

Faster-growing economies are now joining this debt party, believing they can manage it better than their predecessors. History suggests otherwise. The structural problems of the fiat system—its requirement for perpetual growth, its incentives for short-term thinking, and its disconnection from real-world constraints—apply equally to all participants.

As the map starkly illustrates, the question is no longer whether nations will take on more debt, but whether the entire system can sustain the weight of obligations that, by design, can never truly be repaid.