The Great Divide: How Government Spending Shapes Global Economic Landscapes

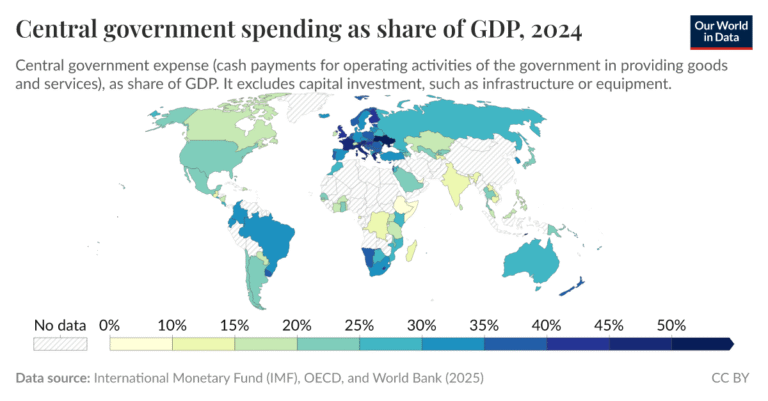

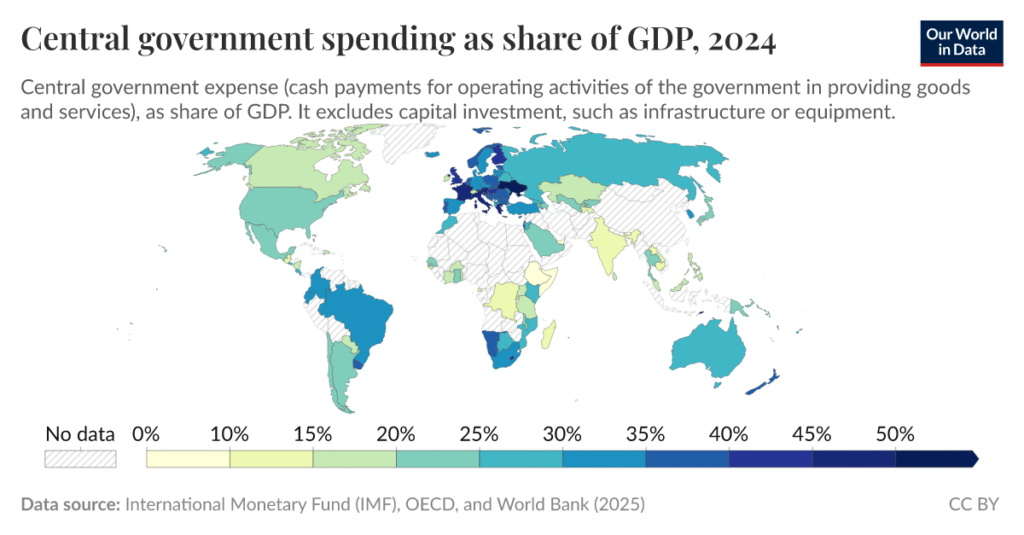

Government spending has long been recognized as a cornerstone of economic activity, but a closer examination of 2024 data reveals a striking paradox: the world’s wealthiest nations rely more heavily on government expenditure as a proportion of their GDP, while developing countries operate with significantly smaller government footprints. This pattern, visible across continents, challenges conventional assumptions about the role of the state in economic development and raises fundamental questions about fiscal capacity, institutional maturity, and the pathways to prosperity.

Europe: The Bastion of Government-Led Economies

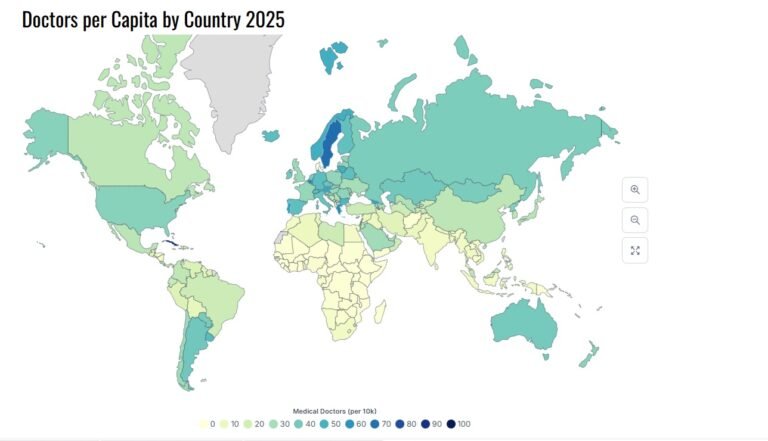

Europe stands as the global leader in government spending relative to GDP, with many nations dedicating between 20% and 30% of their economic output to central government operations. The Nordic countries exemplify this trend, having built comprehensive welfare states that provide cradle-to-grave social services. France, often criticized for its expansive public sector, maintains government spending at similar levels, funding everything from universal healthcare to extensive public education systems.

This European model reflects a deliberate choice made over decades to use government spending as a tool for social cohesion and economic stability. These nations possess robust tax collection systems, mature bureaucracies, and strong institutions capable of efficiently deploying public resources. The high spending levels finance not just basic services but also sophisticated social safety nets, cultural programs, and environmental initiatives that have become hallmarks of European quality of life.

Britain, Germany, and the Benthic countries follow similar patterns, demonstrating that substantial government spending correlates with advanced healthcare systems, excellent infrastructure, and high human development indicators. The European experience suggests that developed economies can sustain higher government spending because they have the administrative capacity to collect taxes effectively and the institutional frameworks to spend those resources productively.

North America: Moderate Spending with Continental Variations

North America presents a more varied picture. The United States, despite its reputation for market-oriented economics, maintains central government spending in the moderate range, typically between 15% and 20% of GDP. This reflects substantial federal expenditures on defense, social security, Medicare, and other major programs, though state and local governments handle many services that European central governments provide directly.

Canada’s spending patterns align closely with European norms, reflecting its more comprehensive public healthcare system and stronger social safety net. The contrast between the United States and Canada illustrates how political culture shapes fiscal policy even among wealthy neighbors with similar economic structures.

Mexico, while geographically part of North America, exhibits spending patterns more characteristic of developing nations, with lower government expenditure as a share of GDP. This partly reflects challenges in tax collection and a large informal economy that escapes taxation, limiting the government’s fiscal capacity despite the country’s middle-income status.

Asia: A Continent of Contrasts

Asia presents perhaps the most dramatic variations in government spending patterns, reflecting the continent’s extraordinary diversity in development levels. Japan and South Korea, as advanced economies, maintain government spending levels comparable to many European nations, funding sophisticated public services and social programs befitting their high-income status.

China occupies an interesting middle ground. While officially a developing country, its government spending patterns reflect its transition toward a more developed economy, with increasing investments in social services, healthcare, and education alongside traditional infrastructure spending.

South and Southeast Asian nations generally operate with much lower government spending relative to GDP. India, despite being the world’s most populous nation and a growing economic power, maintains relatively modest central government spending. This reflects persistent challenges in tax collection, a vast informal sector, and limited state capacity in delivering services across its enormous and diverse territory.

Countries like Bangladesh, Pakistan, and many Southeast Asian nations face similar constraints. Their governments simply cannot mobilize resources at the scale of developed nations, operating instead with lean budgets that struggle to provide even basic services to rapidly growing populations. This creates a vicious cycle: low spending means poor public services and infrastructure, which in turn limits economic growth and tax revenue generation.

Africa: The Challenge of Limited Fiscal Capacity

Africa displays the most acute version of the development-spending paradox. Across the continent, central government spending as a share of GDP typically ranges from 10% to 20%, well below developed country norms. South Africa, as the continent’s most industrialized economy, maintains somewhat higher spending levels, yet even it falls short of European standards.

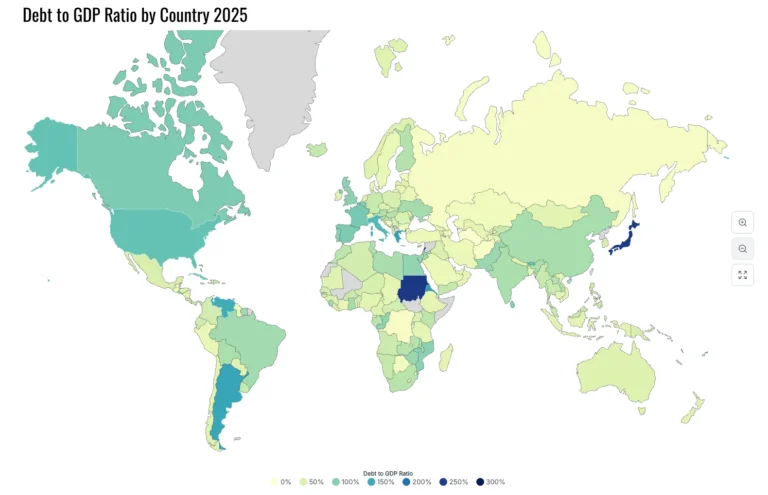

The constraints facing African governments are multifaceted. Weak tax administration, large informal economies, widespread poverty, and limited institutional capacity all combine to restrict revenue collection. Meanwhile, debt burdens and economic volatility force governments to prioritize debt service over developmental spending. The result is a stark inability to provide adequate healthcare, education, infrastructure, and other public goods essential for development.

Countries in the Sahel region, East Africa, and Central Africa face particularly severe challenges. Their governments often control less than 15% of GDP, leaving them unable to respond effectively to humanitarian crises, invest in human capital, or build the infrastructure necessary for economic transformation. International aid partially fills these gaps, but external resources cannot substitute for domestic fiscal capacity.

Latin America: Middle-Income Constraints

Latin America occupies a middle position in global spending patterns, with most countries falling in the 15% to 25% range. Brazil, Argentina, and Chile demonstrate that middle-income countries can sustain moderate government spending levels, funding public services that exceed African or South Asian standards while falling short of European comprehensiveness.

However, Latin American governments face distinct challenges. High inequality means that even moderate spending often fails to reach the poorest citizens effectively. Political instability and periodic economic crises disrupt long-term fiscal planning. Many countries struggle with inefficient tax systems that allow wealthy individuals and corporations to avoid contributing their fair share, constraining government resources despite middle-income status.

Oceania: Following Developed World Patterns

Australia and New Zealand demonstrate spending patterns typical of developed nations, with government expenditure representing significant shares of GDP. These countries have built comprehensive public service systems, including universal healthcare, strong educational institutions, and robust social safety nets. Their geographic isolation and small populations relative to their economies have not prevented them from achieving spending levels comparable to Europe or North America.

The Development Paradox Explained

Why do rich countries spend proportionally more on government than poor countries, when logic might suggest the opposite?

The answer lies in state capacity and the nature of economic development itself. Developed nations possess the institutional infrastructure to collect taxes efficiently, administer complex programs effectively, and deploy resources productively. They have formal economies where transactions are documented and taxable.

Developing countries lack these advantages. With large informal sectors, limited administrative capacity, and weaker institutions, they cannot mobilize resources effectively even when needs are desperate. This creates a development trap: insufficient government investment perpetuates underdevelopment, which in turn prevents the state capacity building necessary for higher spending.

The 2024 data underscores a fundamental truth about economic development: building effective states capable of mobilizing and deploying resources may be as important as any other factor in achieving prosperity. The challenge for developing nations is not simply to increase government spending, but to build the institutional foundations that make higher, more effective spending possible.